by Olof Heggemann

This article first published on legalversemedia.com.

Several litigation analytics tools now claim to be able to predict case outcomes using large databases of past court decisions. These systems are marketed as objective and data-driven. But how trustworthy is the data they rely on as the main predictor?

In this short article, I want to highlight one of the main challenges of relying on court data to predict case outcomes: survivorship bias.

What is survivorship bias?

The classic historical example explaining survivorship bias goes like this:

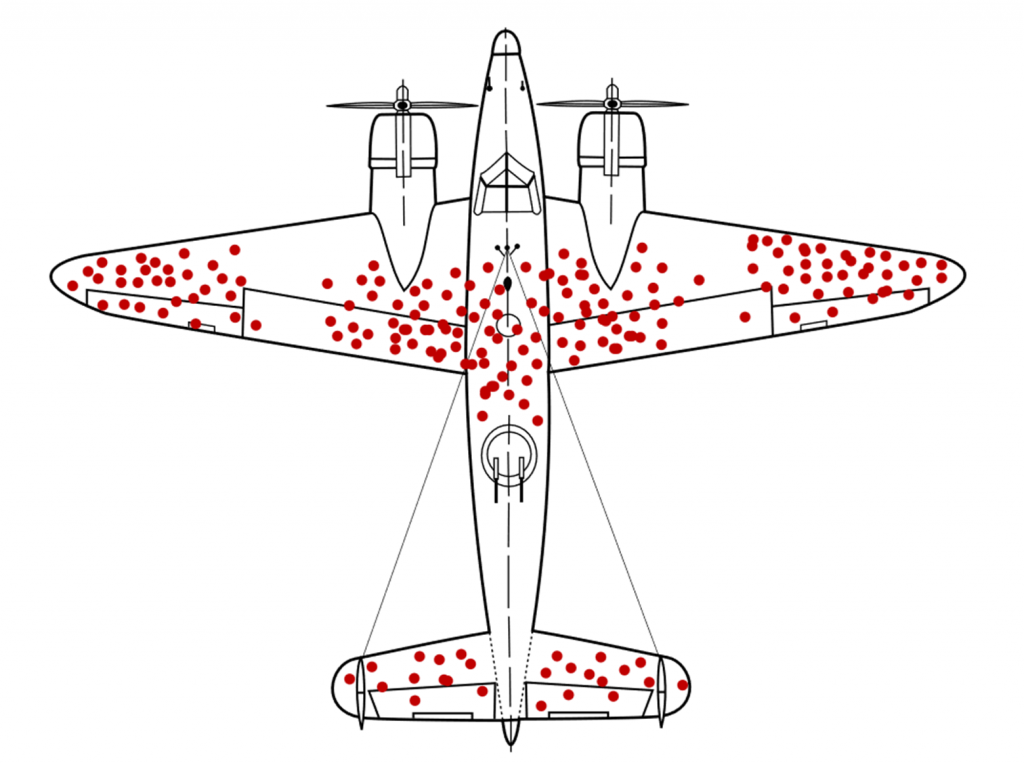

During World War II, the US military wanted to reinforce its bomber planes after suffering heavy losses. They looked at the location of bullet holes on the planes that returned from missions and planned to add extra armor to the areas most often hit. An illustration shows where hits were frequent:

The mathematician Abraham Wald, who was engaged with the project, pointed out a flaw in the military’s reasoning. These were the planes that had survived being hit. The ones that didn’t return — the ones shot down — were perhaps hit elsewhere? Instead of reinforcing the often bullet-riddled areas, Wald suggested reinforcing the areas that showed no damage on the surviving planes.

This is the textbook case of survivorship bias: the risk of drawing conclusions from what is visible, and ignoring what not shown. (Insert footnote).

So, what does this have to do with litigation data?

Let’s bring this back to the courtroom.

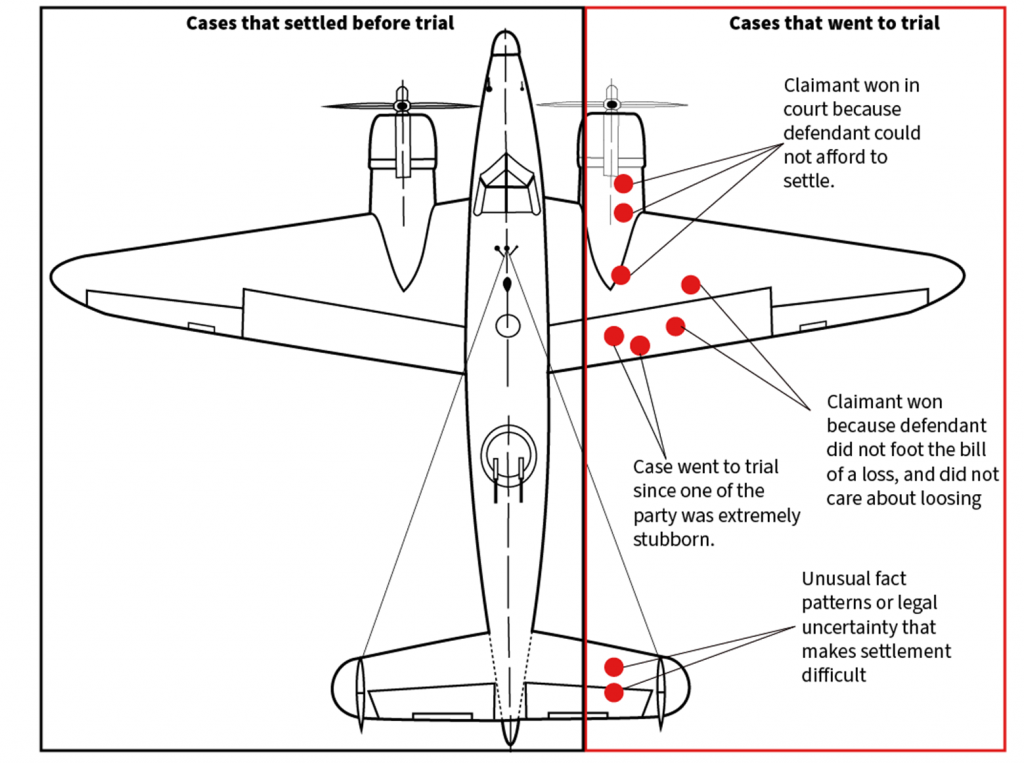

Most litigation databases rely on publicly available court judgments. That means they mainly rely on the cases that made it all the way to trial and received a judgment — the “survivors”.

But this leaves out a huge part of the picture: the many — likely the majority — of disputes that settle along the way. There is good reason to believe that these “surviving” cases are not any random sample. In fact, the cases that don’t settle and are resolved through a judgment are likely to be different in important ways. They could, to a greater extent, include:

- Parties who can’t afford to settle and where their weak financial status is even the real reason for the dispute in the first place

- Cases where one side is stubborn or emotionally invested

- Disputes where an insurer or third party is ultimately footing the bill, so the defendant does not care about putting up a fight

- Parties who gravely misjudge their position or overestimate their chances

- Cases with complex fact patterns or legal uncertainty that makes settlement difficult

In short, the visible cases in the data may systematically differ from the ones that were resolved earlier through a settlement. Just like the bullet holes on surviving planes, they reflect only part of the story — and possibly the wrong part.

Asking the data “Will I win?” might give you a probability of success. But the answer could in fact be for a different question: “If I have an opponent that is too poor to settle, too stubborn to settle, or an unusually complicated case — will I win?”

This could potentially be resolved by including settlement statistics, but anyone who has worked with trying to classify settlements in terms of a “good or bad” outcome will know that this is challenging and likely not practically possible. Some specific areas, such as cases involving class actions, or other matters where initial claims and actual settlements are made public, may be different.

Why this matters for lawyers

If you base your predictions on skewed data, your predictions will be skewed too.

All of this doesn’t mean litigation analytics is useless. But it does mean that tools built mainly on judgment datasets must be used with caution and expertise. They can reinforce existing biases and both underestimate and overestimate risk.

One must remember that the cases in the data that were resolved at trial are not the average dispute. Like the returning aircraft, they could be valuable to study — but only if we remember what information is missing, and that is hard to know. The clearly identifiable areas free of bullet holes are not easily seen in the data.

If you’re curious about assessing disputes and understanding the likely outcomes better, with or without use of data, don’t hesitate to get in touch: info@eperoto.com

— As a side note: The example with Abraham Wald does not show the whole truth. The military was actually aware of the survivorship bias. Wald’s contribution was to model which specific areas of the aircraft should be reinforced using the data available. https://www.cantorsparadise.com/survivorship-bias-and-the-mathematician-who-helped-win-wwii-356b174defa6)