This is the second article in our series on Decision Analysis for Corporate Counsel. You can find the other articles here.

In many complex disputes, risk is still summarized as a single percentage chance of winning, or worse, as a vague descriptor like “strong case.” While this shorthand may be convenient, it’s inadequate for high-stakes decision-making. Litigation rarely resolves as a binary win or loss. Damages may be high, low, or somewhere in between; parties may win some claims and lose others; and costs, interest, and counterclaims can radically alter the net financial impact. Moreover, most cases settle and dispute risk assessments are a key input to settlement negotiations and decisions.

Decision analysis is an established technique to quantify uncertainty, or in our case: litigation risk. It’s not AI or data analytics, but rather a way for attorneys to better express their assessment of the issues, visually and quantitatively. This provides for informed decision making and better corporate governance for resolving litigation.

The Problem with Vague Risk Language

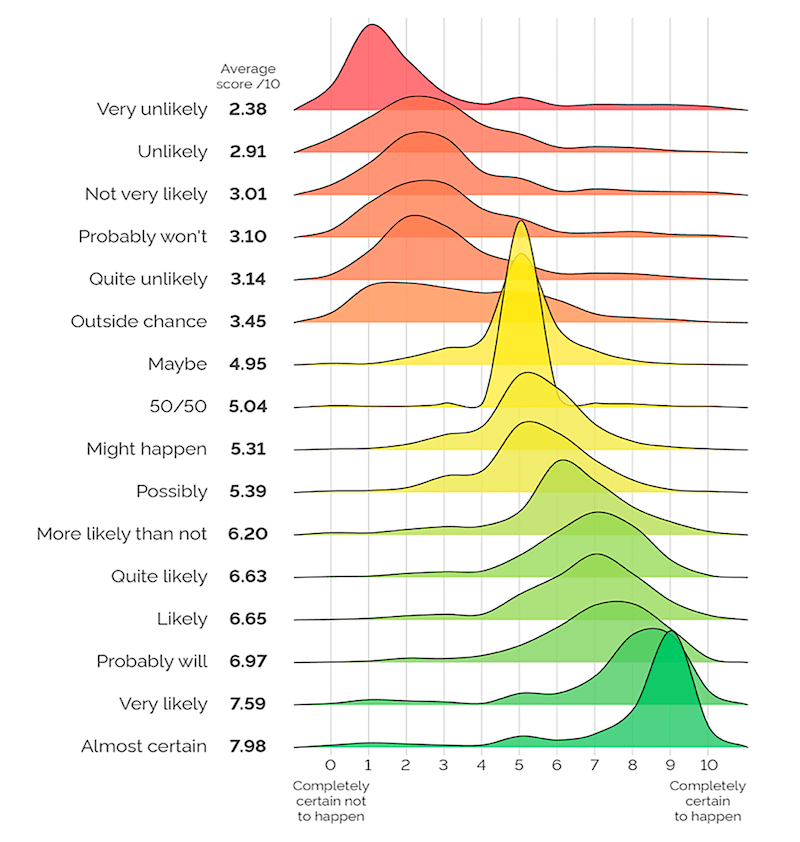

Lawyers often describe litigation risk in broad terms like “strong case” or “reasonable chance” to describe the chances of winning or defeating a claim. While convenient, these phrases are highly ambiguous and many studies have shown they’re prone to wildly different interpretation, even by trained professionals. One lawyer may say a “strong case” is around a 60% chance of success while their client may hear it as 80%.

Yet commercial clients increasingly expect more precision. In a business world driven by quantified risk (credit, cyber, operational), qualitative labels alone now fall short.

Vagueness also prevents accountability. Without numbers or ranges, assumptions can’t be tested, models can’t be updated over time, and boards can’t make informed budget or settlement decisions. Clear, quantified assessments instead help decision-makers take informed risk-based decisions, and help create a learning organization that improves over time.

With that foundation, it becomes clear why even a single win-loss percentage fails to capture the real dynamics of litigation.

The Limits of the Single Percentage

If external counsel are ever required to quantify their assessment of litigation it usually comes in the form of a single percentage chance of success, e.g. “75%”. Lawyers hate providing this and decision makers should hate receiving it. It’s simply not nuanced enough to be of any use except in the most trivial of cases.

As Aaron and Brazil noted in the ABA’s Shaking Decision Trees for Risks and Rewards (2015), “one liability chance and one lump-sum damages estimate would not fairly map the litigation” in a multi-issue case. General Counsel need to see the range of potential outcomes and how likely each is, not just an averaged snapshot.

Even in single-issue cases, awards may be for only partial damages rather than the full claim. Consider a scenario where counsel says there’s a 70% chance of success. Does that mean a 70% chance of winning $50m, or a 70% chance of winning something – possibly as little as $1m – and a 30% chance of losing outright? Without breaking this down, the 70% figure is almost meaningless for budgeting, settlement evaluation, or reserve-setting.

The Perils of Gut Feel

Without structured modelling, assessments rely heavily on intuition. Experienced litigators typically claim they’re able to intuitively assess the important factors and combine them to understand both the chances of success and the likely financial outcomes. But there are (at least) three key problems to this.

Firstly, research shows lawyers are overconfident towards their clients chances. A 2010 study by Goodman-Delahunty et al. found they overestimated their chances of success by an average of 11–15 percentage points. Quantifying confidence levels makes it easier to challenge and discuss estimates at a more detailed level. One can create different scenarios and see their impact: optimistic, best-guess, pessimistic. You can flip the numbers and consider things from the opposing party’s point of view. With vague quantification of risk like “fairly likely” these aren’t really possible. Besides the confidence bias, other cognitive biases also affect us all (conjuction fallacy, anchoring, confirmation bias & more), and performing a more structured assessment is one tool to counteract such biases.

Secondly, most non-trivial cases have multiple uncertainties: different liability findings, damage quantum, cost shifting, perhaps even enforcement risk. For most people, if not everyone, it’s simply not possible to intuitively combine risk across multiple uncertainties and understand the result. As the 2010 article noted, an “intuitive gut calculator cannot know the cumulative probabilities for each possible outcome in a complicated case.” External counsel should provide clear advice for the decision-makers to act, but without a process to combine the different factors the advice is either too detailed (enumerating each factor and a description of the uncertainty) or unreliably summarised (if research shows it’s not possible to do intuitively, do you trust external counsel’s wrapping up of all factors into a single “strong case” assessment).

Thirdly: communication of uncertainty. As discussed earlier, language to describe possible outcomes is interpreted differently by different people. “Very unlikely” means 5% for one person and 30% for another. With multiple people contributing to a dispute assessment (associates, partners, perhaps external experts), the vagueness of a gut feel is magnified through inaccurate communication. Then, even if the legal team who produce the assessment have a crystal clear shared understanding of dispute risk, they don’t have an adequate way to communicate that to the business decision maker. Large litigation decisions typically need buy-in from multiple stakeholders in the business and again, gut feel and vague language is an inadequate tool to convince the board or department heads of a proposed settlement or litigation strategy.

Put simply, gut feel and intuition are excellent for many things, but alone they are inappropriate to justify significant litigation decisions. A structured approach makes sense, is proven, and is relatively easy to apply.

Richer Communication with Decision-Makers

The C-suite and boards are increasingly data-driven. Vague assurances like “we’re in good shape” frustrate business leaders who must make budget, risk, and disclosure decisions. By modelling litigation uncertainty and producing a probability-weighted set of outcomes, counsel can present a clear, defensible picture. Stakeholders can discuss strategy and priorities from an informed perspective, such as what premium it’s worth paying to settle a case early versus litigate all the way. With only a vague assessment of likely outcomes it’s hard to say whether a slim risk of a terrible outcome is acceptable or not.

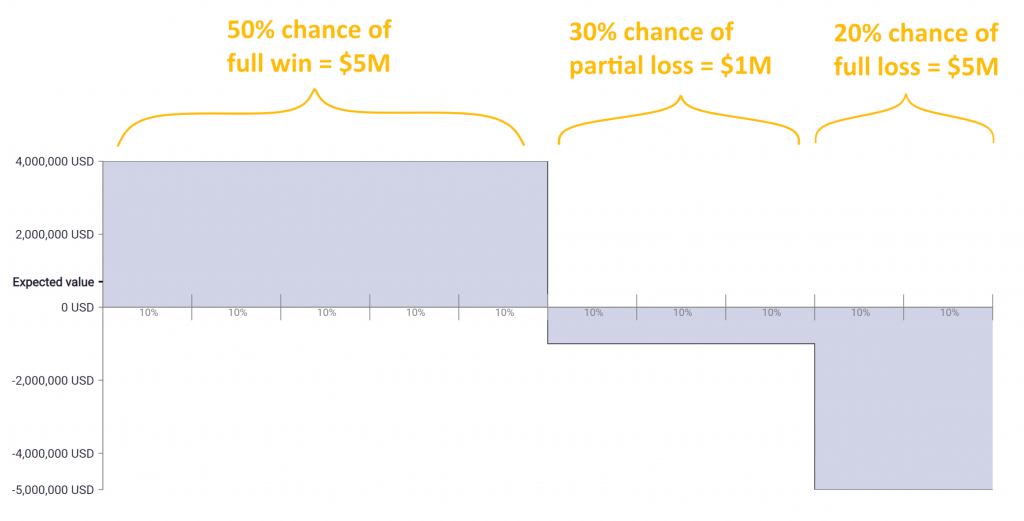

Consider this visualization of a contract dispute with three possible outcomes. Of course we don’t know what will happen at trial, but if counsel provide a summary of their assessment like this it allows decision makers at a glance to see the size and likelihood of possible outcomes. It moves the strategy to being a business decision: do we want to take this risk, what is a good settlement, what are we willing to accept to remove this risk & distraction from our business, or to retain a business relationship with the other party.

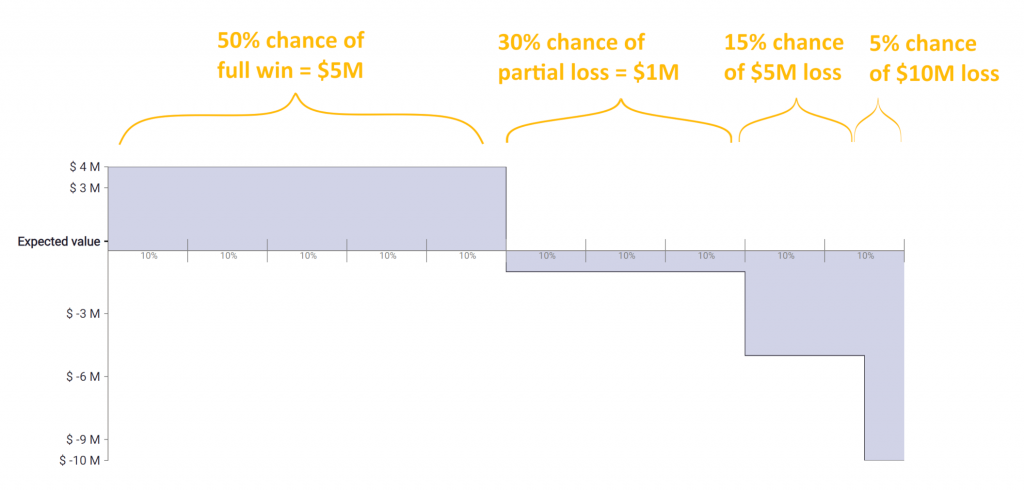

A dispute with the same “chance of winning” but a small chance of a bigger loss might result in quite different discussions and decisions being made:

But without such a clear assessment of risk those decisions are harder to make and harder to justify. A quantified breakdown supports informed board discussion, satisfies auditor scrutiny, and aligns legal advice with corporate risk frameworks.

Better Settlement Strategy

Settlement is where modelling often shows its greatest benefit. A single win probability says nothing about the dollar value at which settlement makes sense. A decision tree can produce a risk-neutral settlement value – the point at which litigating and settling have equivalent expected value.

In decision analysis terms, the “Expected Value” (EV) is the average of all outcomes based on how likely they are. If there’s a 50% chance for a $1M win and a 50% chance of nothing then the EV is $1M x 50% = $500,000. The charts above show the Expected Value for those cases. A risk-neutral person would accept a settlement at or above the EV. Of course, this is just one reference point and it usually doesn’t include factors like employee time spent for any litigation, stress, reputational damage, and so on. But it does provide a useful reference point to assess what a good settlement is.

Relative to the EV you can consider how much additional aspects should be valued, e.g. the EV might be $1M but we’re willing to pay a $0.5M premium to resolve it quickly and without trial. You can also use the EV to show why a settlement achieved during negotiation was a win for the business: “we’re suing them for $10M and settled for $2M but that was twice the EV of going to trial”.

If the EV of a case is +$7m but the realistic outcomes range from a $50m loss to a $40m gain, a GC might reasonably accept a settlement offer below the EV – for example, $5m – to avoid the risk of a large negative outcome. Conversely, if offered significantly more than the EV, such as $10m, it would be an even clearer choice to settle early and secure that upside while avoiding tail risk.

In mediation, sharing a well-supported model can shift the other side’s expectations and provide evidence for a stronger settlement. CEDR’s Commission on Settlement in International Arbitration (2009) noted that quantified assessments often help parties bridge gaps more quickly.

Holding Outside Counsel to a Higher Standard

Some sophisticated clients already insist on quantitative risk analysis. A banking litigation head, after receiving such an analysis, told counsel: “This should be mandatory on all new cases we instruct you on” (Aaron & Brazil, 2015). Companies like ConocoPhillips and LyondellBasell have integrated formal Litigation Risk Analysis processes with their outside counsel, as described in Marc B. Victor’s materials on LRA and ACC case studies.

By requiring decision-tree evaluations and probability-weighted outcomes, GCs not only get better information, they also drive their law firms to focus on the most impactful issues, identify creative resolution opportunities, and think more strategically about resolving the dispute.

Takeaway

A single percentage can’t capture the complexity – or the stakes – of modern commercial disputes. Detailed outcome modelling provides clarity, challenges bias, enhances communication, and strengthens settlement strategy. For GCs tasked with making defensible, high-consequence decisions, it’s not a luxury; it’s a necessity.

At Eperoto we love to talk decision analysis 🙌. Get in touch if you’d like to discuss anything from the articles or you’d like to learn more about Eperoto.

References

Goodman-Delahunty, J., et al. (2010). “Insightful or Wishful: Lawyers’ Ability to Predict Case Outcomes.” Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 16(2), 133–157.

Aaron, M.C., & Brazil, W.D. (2015). “Shaking Decision Trees for Risks and Rewards.” ABA Dispute Resolution Magazine, Fall 2015.

CEDR Commission on Settlement in International Arbitration (2009).

Mnookin, R.H., Peppet, S.R., & Tulumello, A.S. (2000). Beyond Winning: Negotiating to Create Value in Deals and Disputes. Harvard University Press.

YouGov article “How Likely is Likely“, Matthew Smith (2020).